Professor Arline T. Geronimus of the University of Michigan developed the theory of “weathering” while studying health complications of first-time mothers and identifying racial and economic differences.

In early research, Geronimus found white women who gave birth for the first time in their 20s had fewer pregnancy complications than white teenage mothers. Among Black women, the trend was reversed. Many more Black women experienced complications in their 20s as first-time moms than as teenagers. Geronimus wanted to know why, and her pursuit produced groundbreaking research on inequities in American public health.

She was the first to link chronic stress of living with systematic racism to specific health conditions—and how it aged people prematurely. She coined the term “weathering” to address how marginalized communities fare under daily living and economic demands.

In 2023, Geronimus published “Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Ordinary Life in an Unjust Society,” a book rooted in 40 years of research. It makes a bracing case about the toll of societal bias on health. “Healthy aging is a measure not of how well we take care of ourselves but rather how well society treats and takes care of us,” she writes.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

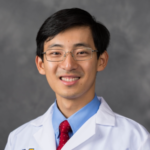

Geronimus and Inside Climate News reporter Nina Dietz discussed climate change and its potential to deepen weathering. Geronimus is a professor of health behavior and health education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health and a research professor in the Population Studies Center there. Geronimus reflected on her early research and how the rising threats from climate change will raise the stakes for marginalized people.

Here is a lightly edited excerpt:

NINA DIETZ: How is climate change compounding the weathering effect among vulnerable populations?

DR. ARLINE GERONIMUS: There’s a lot of ways, both direct and indirect. If you think about weathering as kind of this assault on the body of all kinds of stressors and the need to do high-effort coping to survive them, then you can immediately see several ways that climate change would exacerbate weathering.

One is the way in which the climate itself is getting less hospitable, which is going to affect your body. And so if you’re someone subject to weathering in general, then it’s just another fist in the face when you’re already down. Because weathering isn’t an on/off switch. You can have better or worse outcomes with weathering.

DIETZ: These experiences that prime a person for weathering—are they similar to how collective adverse childhood experiences can predispose individuals to PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) following a trauma?

GERONIMUS: It’s a little different in the sense that weathering is a physiological phenomenon. It reduces your body’s reserves. It makes you vulnerable in all sorts of ways.

You can think of that more at a population level, that these things are socially patterned. It’s not just one idiosyncratic person versus another idiosyncratic person…It is whole populations. That doesn’t mean that every single person in that population is going to be affected, but still, whole populations are affected more than other populations.

So climate change can have very direct physical effects in terms of what it does to the climate and your ability, for example, to keep warm in winter or cool in summer, or to have enough water or food.

And then there are all the uncertainties it poses. If you live where climate change has affected severely, you literally have to move. That’s very destabilizing, but it is also a big part of weathering, having to do what I call high-effort coping.

DIETZ: Can you explain what you mean by high-effort coping?

GERONIMUS: Sure. It’s the fact that you have to endlessly think, “Well, where are we going to live?” or “How are we going to deal with this flood or this natural disaster that’s a result of climate change?” Or having to separate communities and all the confusion and maybe disagreement within families from the constant pressure of wondering, “Should we move, is it safe to stay? What can we afford?”

All of those things contribute to weathering. Both the literal physical parts like toxic environments, or being too hot or too cold, or droughts, or food prices going through the roof so you can’t buy healthy foods. It is just layer upon layer upon layer, where you’re being constantly assaulted by these things. But people don’t necessarily just give up. They have to work harder. Maybe they do three minimum wage jobs so that they can afford food, but get no sleep. Or maybe they’re having to improvise daily routines, as they try to balance taking care of their ailing [relative], and get their kids to daycare, and they still have to get to work on time so they’re not fired.

DIETZ: That must be exhausting.

GERONIMUS: There’s just so much. We talk about juggling … where new needs arise unexpectedly and you can’t just fix it, you get sick, and you can’t just take a day off.

It’s all of those things that lead to high-effort coping, which itself means that your body is running, not just on all cylinders, it’s running on fumes. It’s running on cylinders it doesn’t have—and all of those things exacerbate weathering.

The other part of weathering patterns is that, while maybe you have enough resources to escape the worst ravages of climate change, you may have relatives or parents or people you really care about who don’t. Then, whether or not you managed to physically leave, you haven’t really escaped.

And upward socio-economic mobility was often achieved with the support of those very same people who were left behind. You still care and love and feel responsible for them.

DIETZ: So climate change is just another thing, added to factors already contributing to weathering?

GERONIMUS: I think climate change, to the extent it’s affecting these natural disasters, to the extent that there are islands going and coastlines going underwater, and people are losing their homes, or will be soon, and to the extent you need to migrate, or you have immigrants supporting entire multigenerational families back home with their wages because their land can no longer support farming, these are all ways climate change is exacerbating weathering.

Your responsibilities and the number of people who rely on you, they just go up and up and up. At the same time, your diet is getting worse, your chances to exercise are getting worse, your hours of sleep are not just getting shorter but, because you have all these things to worry about, you’re having poorer quality sleep. We see people whose heart rate is just perpetually up, even while they’re sleeping.

All that weathers your major body systems and erodes your health and leads to you being very vulnerable to all kinds of infectious and chronic diseases, especially autoimmune diseases.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

DIETZ: Why autoimmune diseases in particular?

GERONIMUS: Because it sends your immune system out of whack. And then more people have these diseases at earlier ages and so climate change is, well, a compounding factor with a very big C, you know? All the sequelae of climate change, and all the things that are already happening and especially in places with no municipal infrastructure or no tax base, these are already compounding weathering.

When I was watching the news on the Los Angeles fires, some of the wealthy people in Malibu were saying, ‘I’ll hire my own firemen and take them out of the public workforce.” And you just sort of go, “Wait a minute, what does that do?” …. Weathering isn’t just environmental racism. It’s also about: can you get your problem resolved and in a timely fashion? Do you have the power or resources to do that? I mean, that’s a very big part of weathering.

This also affects your mental health, but the purely physiological things make you so vulnerable to early disease and death. It’s about not being able to put a huge issue to bed and having to constantly be emotionally and cognitively engaged with it. …

Your neuro-endocrine system stays basically aroused throughout that whole time, and that means it’s making your heart beat more quickly. It’s bringing fats and immune cells and sugars into your body, constantly flooding your bloodstream. You get hardened arteries, you get diabetes, you wear down your arteries.

Your immune system keeps your immune cells mobilized in your blood, which is a very good thing when it’s done right or at the right time. For instance, say, when you’re trying to run away from some raging beast. That’s fine. Those sugars give you energy, those immune cells are there if you get mauled, to prevent an infection and jump-start healing.

But if you’re activated all the time, without the raging beast there, and your body’s still doing all of this, then that’s that.

DIETZ: That’s that?

GERONIMUS: That’s how your immune system ends up totally dysregulated. Then you can’t mount a good immune reaction if you get an infection, or you end up with an autoimmune disease, because your immune system is so out of whack.

You know, that stress process is really designed to be on for three minutes.

DIETZ: Why three minutes?

GERONIMUS: That stress response was designed to get you away from a raging beast. Robert Sapolsky [a neuroendocrinology researcher at Stanford University] talks about this. After three minutes, either it’s over, or you’re over. Either you’ve escaped or the raging beast has eaten you.

But this stress response is also triggered by a lot of these social injustices, and they are there chronically. It’s not three minutes, it’s not even three hours, or three days. It could be three months, or even three years. All those physiological processes get set in motion that literally accelerate your aging and wear down your body systems and put strain on your organs.

In a sense, that’s part of why there’s such a strong relationship between weathering and low birth weight, infant mortality and negative pregnancy outcomes (between Black and white women.)

[Weathering explains some] alarming statistics, like a Black mother with a college education has a higher risk of dying in childbirth than a white mother with only a high school education.

It’s because a fetus is the last place the body is going to send oxygen and nutrients, if you’re in a chronic stress arousal state. So people look at Black mothers and, you know, they think, “well, you didn’t get your prenatal care,” or “you didn’t take your vitamins,”or “it’s something you did wrong.” And maybe, if people are generous, they think, “it’s something you couldn’t afford,” or “you didn’t have access to health insurance.” But I only wish it were that simple.

It’s that you’re kind of holding the weight of the world, so to speak, every day, and it’s taking all your bodily resources, and so the poor fetus is not getting what it needs to grow.

Then those babies are at an increased risk for metabolic syndrome and diabetes later in life because of that stress in-utero. These things, they ripple across generations.

DIETZ: Given the sheer number of climate disasters that are happening everywhere, all at once, and the fact that weathering can have this type of generational effect, how does this affect the outlook for already vulnerable communities?

GERONIMUS: I think it can show up in different ways. What I’ve seen is that it can lead to just massive depression and anxiety for some people, this is a case of somewhat individual variation. It can lead to other people becoming politically active and to find meaning in their activities. Other people will decide to just disengage, just to tune out everything. Some choose to engage in radical self care. It’s not that any of these will solve weathering. And in fact, even if you’re doing things like protesting, if you’re doing it kind of night and day, and it’s very personal to you, it can also, ironically, increase your weathering. But people still do it, again, because it does bring meaning.

DIETZ: What are ways that this intersects with climate change, or that could use more research if and when funding this research is a priority again?

GERONIMUS: I think weathering science is at a place where we kind of know what the general categories are. … But do we know why one person is more weathered than another person? Do we know whether it’s exposure to pollution or exposure to biopsychosocial uncertainty and the need for hypervigilance? We can’t say which one is more important. If you could only come up with one policy to have the biggest possible impact on weathering, what would it be? And in some ways, maybe it doesn’t matter when you’re thinking about climate change, because climate change affects all these things.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,