According to the White Helmets, most of the deaths recorded since the fall of the Assad regime took place on former war fronts. Most of the dead were men.

Mr. Talfa took us to two large fields full of landmines. Our car followed him on a long, narrow and winding dirt road. This is the only safe way to reach the fields.

Along the sides of the road, children run around the area. Hasan told us that they are from families that have recently returned. But the dangers of landmines surround them.

As we get out of the car, he points to an obstacle in the distance.

He tells us that in Idlib province, “it was the final point separating areas controlled by government forces from areas held by opposition groups.”

He adds that Assad forces planted thousands of landmines in fields beyond the barriers to prevent rebel forces from advancing.

The fields around which we stand were once prime fields. Today, they are all barren, with no greenery visible except for the green tops of land mines that we can see through binoculars.

Without expertise in clearing mines, all the White Helmets can do is cordon off these fields for now, hammering signs along their borders to warn people.

They paint dirt barriers around the edges of fields and warning messages on houses. “Danger – mines ahead,” they read.

They lead campaigns to raise awareness among local people about the dangers of entering contaminated land.

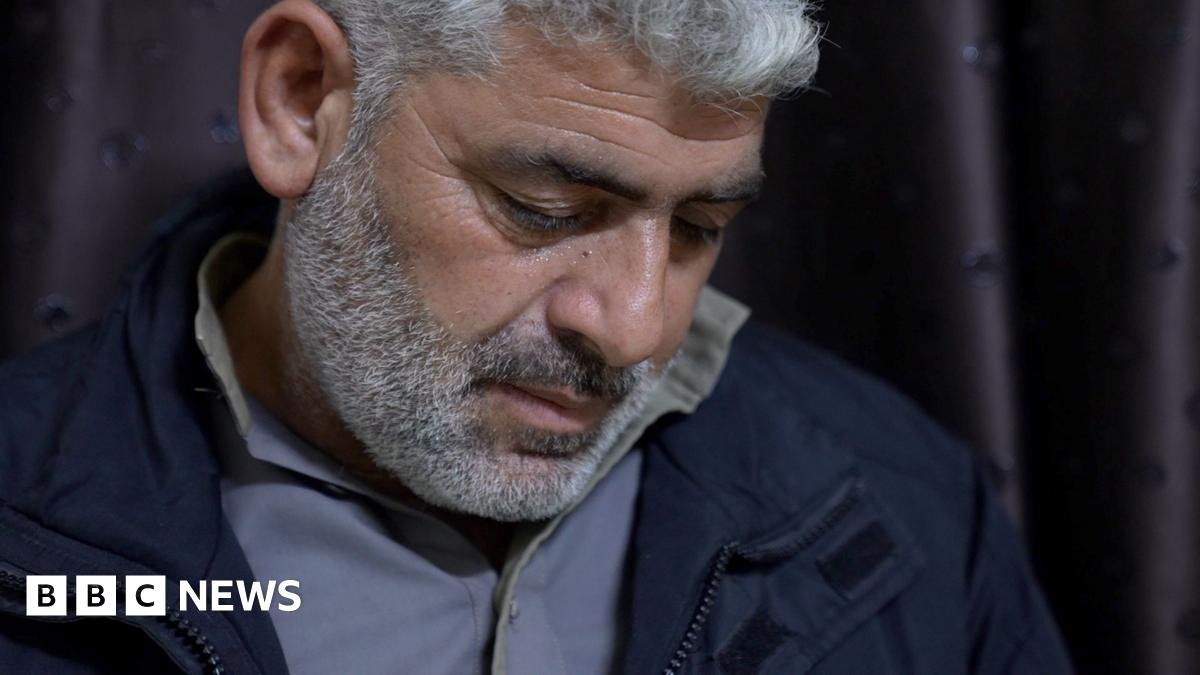

On the way back, we met a farmer in his 30s who has recently returned. He tells that some land belongs to his family.

“We couldn’t recognize any of it,” says Mohammed. “Earlier we used to grow wheat, barley, cumin and cotton. Now we can’t do anything. And until we can cultivate these lands, our economic condition will always be bad,” he adds, clearly frustrated. are