It was around 10 p.m. on a Friday night in Indiana when one young man began messaging with a pretty girl from Indianapolis on a dating app. Lying in bed feeling lonely and bored, he was exhilarated when she suggested they exchange nude photos.

Minutes later, he started violently shaking after the conversation took a turn. The woman was really a cybercriminal in Nigeria – and threatened to expose the nude photographs to his family and friends if he didn’t pay $1,000. The scammer had located his Facebook profile and compiled a photo collage of their sexts, nudes, a portrait from his college graduation and a screenshot of his full name and phone number.

He caved to the threats and sent $300, but a month later, his fears manifested into reality. A childhood friend told him that she had received the nude photos in her Facebook spam inbox.

“I just felt my blood get hot, and my heart went down to the center of the earth,” says the 24-year-old, who requested we withhold his name, citing concerns that the cybercriminals may track him down again and further extort him. “I can’t even begin to describe how embarrassing and humiliating it was.”

He fell victim to a growing crime in the United States: financial sextortion, a form of blackmail where predators convince people to send explicit images or videos, then threaten to release the content unless the person sends a sum of money. In some cases, the crime can happen even if the participant doesn’t send nude photos — the criminals use artificial intelligence to create highly realistic images. The most common victims are young men, particularly teenage boys ages 13 to 17.

Sextortion can lead to mental health problems and in extreme cases death. It’s been connected to at least 30 deaths of teenage boys by suicide since 2021, according to a tally of private cases and the latest FBI numbers from cybersecurity experts.

More than half a dozen young male victims detailed their experiences to USA TODAY and recounted the shame, embarrassment and fear that kept them from telling someone they were being blackmailed or reporting it to the police.

Financial sextortion has exploded since the pandemic

Financial sextortion is the fastest growing cybercrime targeting children in America, according to a report from the Network Contagion Research Institute. It’s likely been around for decades, but in years past people didn’t have the terminology or resources to report it in large numbers, says Lauren Coffren, executive director of the Exploited Children Division at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC).

In the years since the pandemic, reports of the blackmail surged — kids were online more, cybercriminals became more effective, and their operations grew in scale and organization.

In 2022, the FBI issued a public safety alert about “an explosion” of sextortion schemes that targeted more than 3,000 minors that year. Between 2021 and 2023, tips received by NCMEC’s CyberTipline increased by more than 300%. The recently tabulated 2024 numbers reached an all time high, the organization says.

That increase, Coffren says, is because cybercriminals have begun exploiting kids across the globe using the same scripts with each interaction.

One 17-year-old victim, who traced his blackmailer to Nigeria, says it’s “really frustrating” to navigate prosecution options. Another teen, whose predator was based in the Philippines, described the cyber abuse he experienced as “torture.”

“Even now, my blackmailer sometimes tries to contact me, but nothing has been shared because he would lose his leverage,” the second teen says.

The increased prevalence of this crime is also reflected by a surge in victims looking for support. Searches for “Sextortion” on Google have increased five-fold over the last 10 years. One of the largest financial sextortion support forums, r/Sextortion on Reddit, has grown to 33,000 members since its creation in 2020.

Of forum posts that included gender information, 98% were male, according to a 2022 study of the thread. The thread’s main moderator, u/the_orig_odd_couple, says in the last two years, there’s been a noticeable uptick in posts from victims who are under 18.

Because predators are often located abroad, these crimes typically land with the FBI. The organization declined to comment.

Online sexual exploitation can have long-term mental health effects

Teens are relying more on online friends than ever, and regularly feel comfortable disclosing information to an online friend that they may not tell a physical one, according to Melissa Stroebel, the vice president of research and insights at Thorn, a technology nonprofit organization that creates products to shield children from sexual abuse. In 2023, more than 1 in 3 minors reported having an online sexual interaction.

Roughly 25% of sextortion is financial. Ninety percent of financial sextortion victims are males between 13 and 17, according to the NCMEC. Boys have a lower likelihood of disclosing victimization regarding sexual abuse but have higher risk taking tendencies when it comes to sexual and romantic exploration in their teens, creating a perfect storm for blackmailers. Boys also aren’t featured as often in sexual abuse prevention conversations and materials, according to Stroebel.

“It’s really distinctly and disproportionately targeting that community,” says Stroebel. “Criminals are banking on the fact that they might have more success here.”

Because the human brain doesn’t finish developing until around age 25, young people respond to stress and decision making differently than adults, impacting their ability to navigate these scams.

“Fear can compound and become very overwhelming in their brains, and then things start to feel bigger and bigger and bigger,” explained The Jed Foundation Senior Director of Clinical Advising Dr. Katie Hurley. “Because often the threats are not just to themselves, but to other people they know, it feels like an intense amount of responsibility, and that’s where they get frozen.”

Early experiences of abuse have long-term impacts on their ability to build healthy relationships and establish trust with significant others in the future. Victims may develop anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and are more prone to future experiences of online abuse, according to Laura Palumbo, communications director for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

“Emotionally, the worst thing is not even the images themselves, it’s the feeling of knowing that someone is after me with very, very bad intentions,” says the 17-year-old male victim.

Another male, who was just 13 years old when he was sextorted, says it took five years for the guilt and fear to subside.

Teen boys blackmailed using nude photos is on the rise: What to know

Predators financially extort teens, mostly boys, by blackmailing them with nude photos. Here’s what these conversations look like.

‘Hey I have ur nudes’

The exploitation typically starts with what seems like an innocent message through Instagram or Snapchat: “Hey there! I found your page through suggested friends.” The predator will direct the conversation to a sexual nature, and in some cases, send unsolicited nudes — often with the pressure or ask that the teen they are messaging exchange their own back.

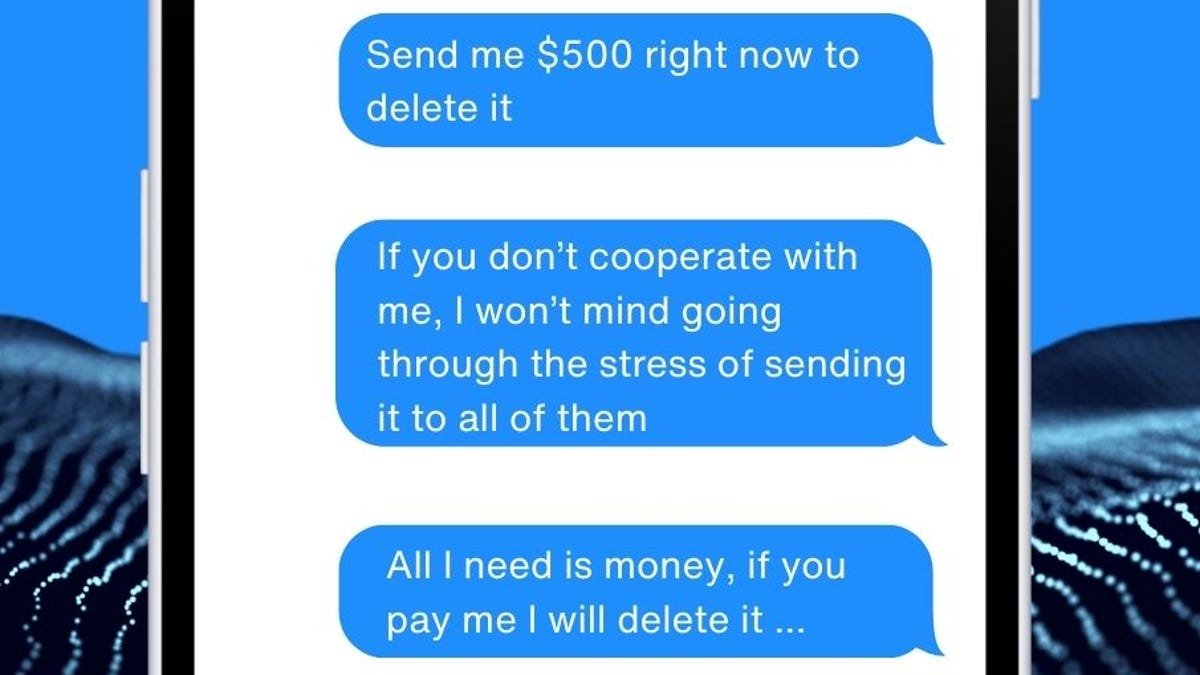

Then, the blackmail starts. Scammers ask for an amount, most commonly $500, to delete the images — or risk them being sent to the victim’s friends and family.

To heighten these feelings of intimidation, criminals often create a countdown of how long victims have to send money, spamming teens with dozens of threats over the course of minutes or hours. The 17-year-old who spoke to USA TODAY says his abuser threatened to share the photos with child porn websites and live camera porn sites, while other blackmailers falsely told their victims they would become registered sex offenders; the act of grooming minor victims in order to receive nudes is illegal in the U.S.

Dozens of scripts obtained by USA TODAY outlined how extortionists create a sense of isolation and manipulate young victims.

“Hey I have ur nudes and everything needed to ruin your life, I have screenshot all ur followers and tags and those that comment on ur post. If you don’t cooperate with me, I won’t mind going through the stress of sending it to all of them,” one script read.

In reality, the account sending these messages is often a team of three to four foreign cybercriminals who simultaneously contact the victim, handle a money transfer, and conduct open source research on the victim to find their family members, contacts and school.

Financial sextortion has often been traced to scammers in West African countries, including Nigeria and Ivory Coast, and Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines, according to the FBI.

For teens on social media, it should raise alarms if the person they receive a message from doesn’t share mutual friends and if a profile’s photos look unusual, blurry or highly-edited. In other cases, the Instagram accounts are highly believable, having been hacked from a real teenage girl or curated with photos over months.

A 14-year-old who spoke to USA TODAY said he initially had suspicions about the account that sextorted him — the user was posing as a 15-year-old girl based in California, but only followed 26 people, and didn’t have any mutual followers.

Since scammers may be non-native English speakers, poor grammar or unusual vernacular can also be a tip off of someone taking on a fake identity.

Teens should also be alarmed if a new follower immediately guides a conversation to a romantic or sexual nature and should be wary of someone asking to move the conversation off of social media onto a private text platform. Predators typically send unsolicited nudes within minutes, according to Coffren.

“This is a romance scam on steroids,” says cyber intelligence analyst Paul Raffil. “They are, within an hour, convincing these kids that they are trustworthy, that they can do something that potentially compromises themselves.”

Scammers have also abused the rise of generative artificial intelligence tools to create highly realistic deepfake images and videos. Roughly one of 10 reports Thorn reviewed involved artificially-generated content.

Here’s what to do if you or your teen is sextorted

Experts say victims should report the predator’s account, but keep their own account and documentation of all messages. Having a paper trail of time frames and messages can be vital in finding a criminal’s identity.

If a predator is going to send out images, it will typically happen within two weeks of contact. Once the images are sent out, the blackmailer loses their leverage and normally moves on, according to Coffren.

Victims should report any attempt at sextortion to NCMEC’s CyberTipline, contact their local FBI field office, or report to the FBI at tips.fbi.gov. Teens experiencing sextortion should tell a trusted adult. For immediate mental health instance, teens can also call or text the the 988 suicide hotline.

Those who have been scammed can work to remove the images from the internet through NCMEC’s Take It Down service, which works by assigning a digital fingerprint called a hash value to a reported sexually explicit photo or video from a minor. These hash values allow online platforms to remove the content, without the original image or video ever being viewed.

Experts agree telling teens to avoid social media platforms or not engage with strangers online is outdated advice given the sheer scale of the problem. Stroebel adds sex shaming teen boys can inadvertently backfire. What’s more, a child could be blackmailed regardless of whether or not they’ve shared a nude image to begin with.

Parents should employ a mentality of discussing online exploitation “before it happens in case it happens,” Coffren says.

One male, who was 23 at the time of blackmail, urged other victims to tell their parents. He panicked over “how stupid” he was after a scammer contacted him on Instagram, but says his parents helped him navigate how to ignore his blackmailer and stay calm — and they blamed the predator, not their son, for what happened.

“Sextortion can happen to anyone. If it happens to you, please tell someone,” he says. “They will support you and be sympathetic.”

This article is the first in an ongoing USA TODAY series investigating a surge in financial sextortion and its mental health impact on teenage boys, which was connected to suicide in extreme cases.

Rachel Hale’s role covering youth mental health at USA TODAY is funded by a grant from Pivotal Ventures. Pivotal Ventures does not provide editorial input. Reach her at rhale@usatoday.com and @rachelleighhale on X.