As COVID surged and schools across the U.S. shuttered in March 2020, Jamie Wyss, an elementary school counselor at the Virginia Beach City Public Schools system in Virginia, vividly remembers quickly assembling paper packets on social-emotional learning to hand out to parents. She initially thought students and staff would return in a week, maybe two. But neither parents nor students would come back to the system’s campuses for the rest of the school year.

“I promised them that I would always be there for them,” Wyss says. “Honestly, it felt like I abandoned my students.”

Nothing could have prepared Wyss or her fellow educators for what came next. Health care facilities were quickly overwhelmed, and governments around the world enacted stay-at-home orders, or “lockdowns,” as millions of people became infected with the COVID-causing coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. As of today, COVID has claimed more than seven million lives globally. Amid this devastating loss, children grappled with sudden social isolation, emotional distress and new academic pressures involved in learning remotely. Teachers, suddenly pivoting to online instruction, were thrust into unpredictable territory. Parents had to balance surviving a deadly pandemic and raising their kids in a massively altered world.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Kids look to us adults to be their stabilizing force—and as adults, we were also really struggling,” says Elizabeth Reichert, a child psychologist and co-director of the Stanford Parenting Center.

The turbulent times took a massive toll on the U.S. education system, with student support varying dramatically among states, school districts and communities. Five years later, the pandemic’s emotional and educational scars are still felt by kids who are reaching their teenage years or early adulthood, leaving experts wondering about lasting effects.

“The decisions [to close schools] were made to protect society, and there was going to be a cost,” says Candice Odgers, a quantitative and developmental psychologist specializing in adolescent mental health at the University of California, Irvine. “There was going to be a cost to children’s learning, and that seemed to be part of the calculus that was being made.”

Growing Gaps in Learning

Student academic performance had been declining before 2020, but math and reading scores dipped even further during the pandemic. In the fall of 2021 mean math scores among third to eighth graders dropped by 0.2 to 0.27 standard deviations, and average reading scores among these students decreased by 0.09 to 0.18 standard deviations compared with same-grade peers in 2019, according to a 2022 report by the Brookings Institution.

Discrepancies in math and reading weren’t felt equally among communities, however, Odgers says. “What we really saw with COVID was a hit for the entire population on learning,” she adds, “but children in the least-equipped and least-resourced schools were hit the hardest.”

In a 2023 study, Odgers and her colleagues surveyed elementary school teachers in the U.S. and Canada about student performance during the 2020–2021 school year. In classrooms with high-income students, 40 percent of teachers reported a performance drop. In those with lower-income students, the proportion was more than 70 percent. The study also found that students from lower-income households were nearly twice as likely to lack teachers with prior online instruction experience and adult learning support at home.

The latest data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences show 49 percent of public school students overall were behind their grade level in at least one academic subject at the start of the 2022–2023 school year compared with 36 percent before the pandemic. In high-poverty communities, 61 percent of public school students were behind their grade level. The 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress, also called the Nation’s Report Card, showed slight improvements in math for eighth graders from well-resourced families and schools—but testing scores of those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and marginalized communities dipped or remained unchanged compared with 2022.

“If we don’t concentrate on social-emotional learning, then we’re probably not going to see as fast of an improvement in academics as we want.” —Jamie Wyss, elementary school counselor

Schools and educators have been tackling learning gaps in multiple ways, such as reducing class sizes and extending the academic year. For example, in July 2023 the Richmond Public Schools district in Virginia ran a pilot program that added 20 days to the school calendars of two elementary schools. The initial results indicated an increase in literacy levels and student attendance at the end of the year, according to district superintendents.

The academic performance data are alarming, and they’re interlocked with another challenge: youth mental health.

“If we don’t concentrate on social-emotional learning, then we’re probably not going to see as fast of an improvement in academics as we want,” Wyss says. “Trust me, if a child is upset sitting in the classroom, they are not going to be listening to math.”

Mental Health Ramifications

Young people’s ability to cope with the emotional and social stress of the pandemic varied among age groups. Students who were in kindergarten when the pandemic began are now on the cusp of middle school—and adolescence. “Our [current] fifth graders lost about two years of social-emotional learning,” Wyss says. Among this group, she says, she has observed behaviors more commonly seen in younger grades. For instance, Wyss has noticed an increase in sensory-seeking behavior (touching others more frequently), a lack of self-awareness (not noticing they’re wearing a shirt inside out) and difficulty with reading social situations. “They lost those two super important years [of peer interaction] in the first and second grade, where they were learning what’s socially acceptable and what’s not,” she says.

Meanwhile today’s teens, who were in elementary or middle school during the lockdowns, face other challenges—including changes in brain development that typically occur later in life. A 2024 study at the University of Washington looked at the cerebral cortices of young people aged 12 to 20 in 2018 and 2021 and found preliminary signs of abnormal structural changes at the latter time. The cerebral cortex plays a crucial role in cognition, social interaction and emotional regulation. As the brain develops in adolescence, neurons are naturally pruned back, and cortex thickness decreases. The 54 study participants whose brain was scanned after the pandemic showed accelerated cortical thinning—a sign of rapid brain maturation. Other brain studies of teens who experienced pandemic isolation corroborate the general findings. Corrigan and her colleagues’ study also highlighted striking differences in sex, however.

“In males, it looked like the brains were a year and a half older, whereas for females, they looked more than four years older, on average, than typical development,” says study co-author Neva Corrigan, a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences.

Accelerated cortical thinning, which is well documented in children who have experienced a severely stressful life event, is associated with an increased risk of developing neuropsychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression. It’s not clear if the pandemic was the primary cause of the cortical thinning recorded in the 2024 study at the University of Washington, and researchers don’t know if the changes are permanent. Corrigan says it will be crucial to keep an eye on adolescents because they may require extra support.

“We knew that anxiety and depression really skyrocketed during the pandemic, and there are many studies showing that it was much more severe for females than males,” Corrigan says. “Now, notably, these trends seem to have continued even after the lockdowns ended.”

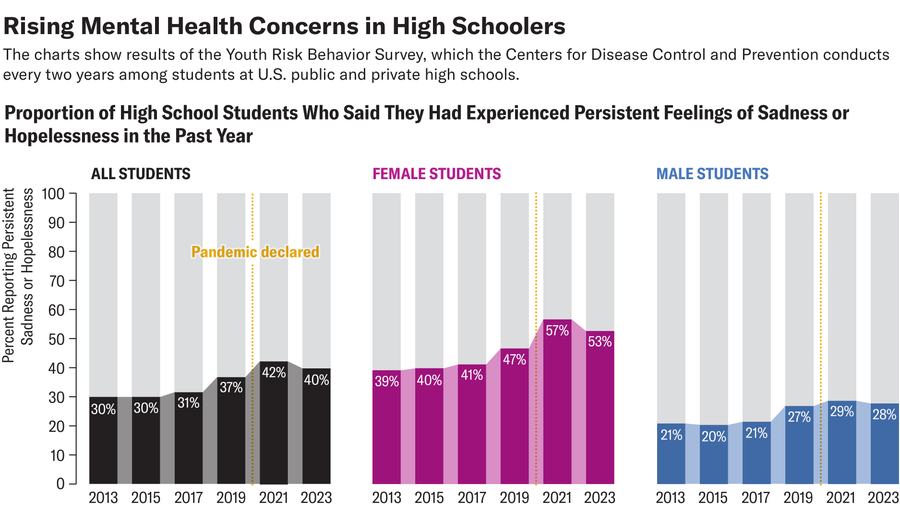

Amanda Montañez; Source: Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024 (data)

The 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that four in 10 high schoolers experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness and that two in 10 considered attempting suicide. Overall, in 40 percent of high schoolers, the severity of mental health issues caused them to withdraw from their regular activities.

Chronic absenteeism (missing 10 percent or more school days in a year) spiked during remote learning and remains a struggle: the Department of Education reported average national rates at 31 percent in the 2021–2022 school year and 28 percent in the following year, compared with 17 percent in the 2018–2019 school year. Some states saw rates as high as 47 percent. Wyss says growing student apathy may be another factor. “Children realized, ‘I don’t have to get on a bus and go to school to learn. So why are you making me do that now?’” Wyss says. “Students lost trust in the educational system, and adults did, too.”

Building Resilience

Research shows the well-being of parents, teachers and other adults directly affects that of kids. Last year the U.S. surgeon general released a report highlighting the enormous stress and burdens placed on parents and the need for more support for caregivers of children. Teachers, too, have shown increased burnout—with the rate of teacher absences and demand for substitutes on the rise.

“The health of our children is intrinsically tied to the health of the adults around them,” Odgers says. “Solutions are going to involve not just investments in children but [also] investments in families and schools.”

Studies suggest that interventions focused only on children produce some gains but that providing support for a whole family leads to greater improvements in both learning and mental health, Odgers says. At the Stanford Parenting Center, Reichert, along with co-director and child psychiatrist Mari Kurahashi, created a webinar series to help parents with pandemic-focused caregiving strategies, from facilitating family communication during a crisis to managing screen use and transitioning into and out of remote learning.

“One of the guiding principles that we follow across a lot of different parenting programs—that’s based on decades of research—is balance in parenting,” Kurahashi says. “Balance being supportive, warm, validating, affectionate and, at the very same time, being firm, having lots of limits, setting consistency.”

Reichert and Kurahashi say parents have been emphasizing affection a lot more lately. “In this post-COVID time, so many parents have kind of leaned more toward the warmth, the love … and then really, really relaxing on the rules,” Reichert says. Children have “gone through this really hard time, and now we want them to just be able to kind of live their lives.” But she and Kurahashi encourage reestablishing boundaries, particularly around screen time—which spiked during the pandemic.

“Kids are more resilient than we give them credit for.” —Elizabeth Reichert, child psychologist

Kurahashi also stresses the need to listen deeply to children, encourage them to ask questions and validate their feelings and experiences. Wyss agrees that adults must show compassion. If a child is not “acting their age,” pause before reacting. “Staff members or teachers can make assumptions about what students are doing and why they’re doing it, and you can’t generalize a behavior to all children,” Wyss says.

Mental health and learning setbacks in youth have become high-profile consequences of the pandemic, but educators and experts emphasize the need to avoid holding these challenges against young people. “Overpathologizing a whole generation can have a really negative impact, especially given that children and adolescents are so impressionable,” Kurahashi says.

She and Reichert note that many patients in their respective practices have come out of the pandemic stronger—an achievement that shouldn’t be overlooked. “While COVID was a very stressful time, it also was an opportunity for a lot of children, teens and families to grow in their resilience and develop coping skills,” Reichert says. “Kids are more resilient than we give them credit for.”

Odgers cringes at terms like “the pandemic generation” and urges people to stop using labels that oversimplify a complex situation.

“There is a harm story to be told from this, and there’s a resilience story to be told from this. And both can be true at the same time,” she says. “We have to be careful that we look with a little more nuance and skepticism about what the long-run impacts of this really will be and not to write off an entire generation of young people as lost—because they are not.”

IF YOU NEED HELP

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or use the online Lifeline Chat.

![Chromecast (2nd gen) and Audio cannot Cast in 'Untrusted' outage [Update]](https://newsplusglobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/1741746771_Chromecast-2nd-gen-and-Audio-cannot-Cast-in-Untrusted-outage-150x150.jpg)