SEOUL, South Korea – Few people understand what goes through the minds of North Korean soldiers fighting for and for Russia in the war against Ukraine. But Lee Chul Yoon is one of them.

Lee, 38, a North Korean defector and ex-soldier now based in South Korea, said it was “devastated” to see soldiers from the communist-ruled North sent overseas by leader Kim Jong-un. Who” is, “then they have to abandon the youth for a land that is not theirs but a foreign land of Russia.

He is one of several defectors who spoke to NBC News about the training, conditions and mindset of North Korean soldiers, including their willingness to take their own lives if necessary.

Lee said his former comrades were “basically just sent cannon fodder to the front lines.”

For the first time since arriving in Russia in the fall, North Korean soldiers have been captured alive by Ukrainian forces, with video and photos showing one man with bandages around his jaw and another bandaged. Shown by hands.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who announced the prisoners’ concerns earlier this month, said they were living proof that North Korea had entered a major escalation of the years-long conflict.

The US and allies say more than 11,000 North Korean troops are fighting in the Russian region of Kursk, where Ukrainian forces launched a cross-border offensive in August. Neither Moscow nor Pyongyang have confirmed these reports.

“Honestly, capturing a North Korean soldier is not easy,” Ryu Sang-hyo said in an interview in the South Korean capital, Seoul.

All North Korean recruits are taught a song that includes a verse about saving their last bullet to avoid capture, said Ryu, who served in the North Korean military until 2019. Hai, who served in the North Korean military until 2019, when he escaped to freedom in South Korea.

According to South Korea’s National Intelligence Service, there was at least one recent incident in which a North Korean soldier, facing possible capture by Ukrainian forces, detonated a grenade while shouting Kim’s name. He tried to do this but was killed before he could succeed.

South Korea’s military said last week that North Korea was preparing to send additional troops to Russia after nearly 300 of its soldiers were killed and 2,700 others injured. South Korean lawmakers said the high casualty rate was due to the soldiers’ poor understanding of modern warfare, as well as the way they were deployed by Russia.

Their willingness to fight and die for Russia could be a major factor in determining the course of the Ukraine war, as well as the level of US military aid to Ukraine under President Donald Trump, who has continued to support US support. But doubts have been expressed.

Kim is believed to be providing military and weapons supplies to Russian President Vladimir Putin in hopes of getting technical support for his nuclear and ballistic missile programs. Its weapons testing spree continues with three launches already this year, including multiple short-range ballistic missiles, a new hypersonic intermediate-range missile and a strategic cruise missile.

Trump drew criticism from South Korea on Tuesday after he described it as a “nuclear power,” a phrase long used by U.S. officials. Avoidance, as it could signal recognition of North Korea as a nuclear-armed state.

Kim is sending troops to Russia for two reasons, “both driven by desperation,” said Ahn Chan-il, who served in North Korea’s military for more than a decade and defected to South Korea in 1979. was denied in Korea. First is to earn foreign. The currency, which is under UN sanctions imposed on North Korea over its weapons programs, is in delivery.

The deployment also provides valuable experience for the North Korean military, which has not been stationed overseas since the Vietnam War.

Dorothy Camille-Shea, deputy US ambassador to the United Nations, told the Security Council this month that fighting alongside Russia would enable North Korea to “fight a war against its neighbors.”

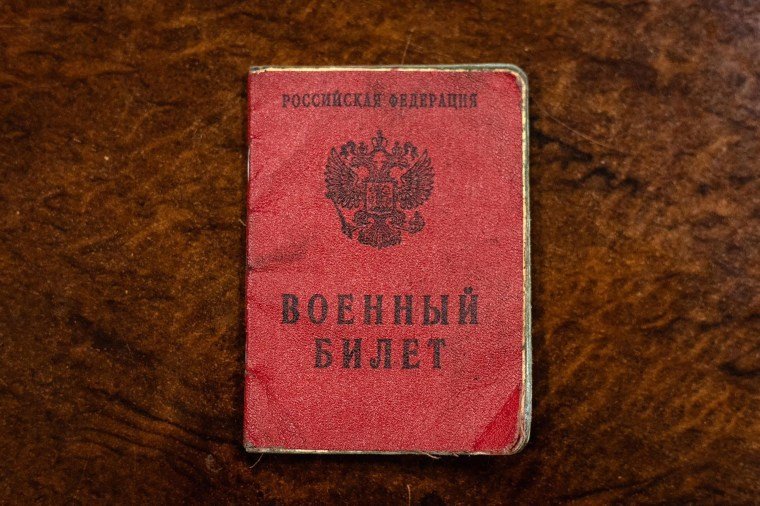

Lee, who spent five years in the North Korean military, said the soldiers were sent to Russia as mercenaries rather than soldiers, saying they did not wear their uniforms. South Korea’s National Intelligence Service has said they were given Russian military uniforms and Russian-made weapons along with fake identification documents.

“Even if they die there, it doesn’t matter, because North Korea sent them out without official recognition,” Lee said. “They were sent there not to bring honor to the country, but to give up their lives and bring back a lot of money.”

‘No longer a part of society’

Military service is compulsory in North Korea, which has the largest standing army in the world. The soldiers, who arrived in South Korea in 2016 after swimming six hours from the North, said the soldiers underwent three months of basic training before being assigned to a unit.

“As soldiers,” Lee said, “they are told that they are individuals who are no longer part of society and their families, and must follow the orders of the supreme leader.” “

He has no trouble believing it, Lee said, having been indoctrinated by North Korean propaganda since childhood.

North Korean soldiers spend most of their time not actually being soldiers, but working on farms and construction projects, Lee and others said.

“I think I only fired three rounds a year,” said Lee Hyun-seong, who served in the North Korean military for more than three years. “We had more like 20 bullets,” he said when he moved to a more elite unit.

Asked if he thought North Korean forces could help Russia win the war, Lee – whose family was defamed in 2014 and now lives in the US – was skeptical.

“Honestly, I’m not so sure,” he said, “because I know their training and I know they’re not well trained.” “

For North Korean soldiers, who receive food and clothing but are otherwise essentially unpaid, the main enemy is hunger.

North Korea is struggling with food shortages as Kim devotes most of his resources to his weapons programs, meaning that, like much of the wider population, the military is undernourished and here until they die of hunger.

The food is mainly made of plain rice, corn or potatoes, sometimes mixed with grass or even tree bark, said Lee Chin-yul.

He said his feelings about North Korea changed slowly, largely because of his exposure to foreign media that flow into the country despite the regime’s strict controls – “James Bond” 1990 was his favorite growing up in the 1990s. More recently, the North Korean government has become alarmed by the popularity of South Korean TV dramas, sentencing two teenagers to 12 years of hard labor for watching them.

“When I look at the North Korean fare sent to Russia, I wonder if they would still be involved if they saw so much foreign media in North Korea,” Lee said. “I also wonder if the North Korean government and Kim Jong-un’s dictatorship will still exist.”

Defectors say they hope North Korean troops fighting in Russia will take the opportunity to leave.

“When North Korean workers, who have been trapped in a restrictive system their entire lives, experience life abroad, they see North Korea as nothing less than a prison,” Ahn said. “Once they realize what freedom can mean, it’s hard to imagine that they won’t consider breaking free to live a free life.”

In addition to seeking independence, they can provide the U.S. and others with valuable intelligence about the North Korean military’s tactics and capabilities, which are often exaggerated by the North Korean government.

Ahn and other North Koreans who have denied being soldiers have offered their help to Ukraine against North Korean troops.

“However, instead of directly participating in war, our focus is on psychological warfare to change the mentality of North Korean soldiers,” he said. “Through platforms like YouTube or leaflets, we aim to convey messages to North Korean soldiers, urging them not to die senselessly and instead seek freedom.”

Meanwhile, they watch with heavy hearts as the casualties among North Korean soldiers whose experiences they know only too well.

“These young men didn’t go knowing they were going to die,” Lee said, “but they died because they didn’t know.”

Janice Mickey Fryer and Stella Kim reported from Seoul, South Korea, and Jennifer Jett reported from Hong Kong.