CNN

—

It’s 1962. Cold War tensions bristle between Washington and Moscow. Forced to enlist by the United States military, a young physician reluctantly cuts short his medical residency at New York’s Bellevue Hospital and ships out to a remote corner of Greenland.

His orders? To serve as camp doctor at what he was told was a polar research station dug about 26.2 feet (8 meters) beneath the surface of Greenland’s ice sheet.

Uncle Sam “sent me to sit under the ice cap 800 miles (about 1,300 kilometers) from the North Pole,” recalled Dr. Robert Weiss, who was then 26 and is now the Donald Guthrie Professor of Urology at Yale University.

In fact, Camp Century, as Weiss’ icy home was known, formed part of a top-secret attempt by the US to hide launch sites for missiles in the Arctic, which the military viewed as a strategic location closer to Russia.

Weiss, who said he was unaware of the Pentagon’s ambitious plans until information was declassified in the mid-1990s, has vivid memories of two formative tours of duty at Camp Century in 1962 and 1963. He spent just short of a year there in total, living in a nuclear-powered city in the ice for months at a time.

While the camp’s Cold War importance was fleeting — the US military abandoned Camp Century in the late 1960s after less than a decade in operation — the cutting-edge scientific work conducted there, in fields such as geophysics and paleoclimatology, has had enduring impacts. And the research station’s story isn’t over yet.

Winter snowfall still outpaces summer melt at Camp Century, an experiment in its own right that now lies buried at least 98.4 feet (30 meters) below the surface. However, should that climate-driven dynamic flip, some potentially harmful remnants of the site could emerge, posing an environmental hazard that authorities haven’t grappled with, according to several studies conducted over the past decade.

Only a few firsthand accounts of living at Camp Century have been published. Weiss said he felt compelled to share his memories after friends passed along a blog post published in November that included stunning new imagery of the camp taken by NASA scientists as they conducted an aerial survey of Greenland’s ice sheet. Captured with the help of sophisticated radar mapping technology, the overhead view reveals the specter of structures submerged within the ice and a life only a few like Weiss could intimately describe.

Camp Century was a Cold War Arctic research base built by the US military.

Building a “city under the ice,” as Camp Century has been called, was an unprecedented feat of engineering. Polar research stations today are typically built on top of the ice rather than hollowed out underneath.

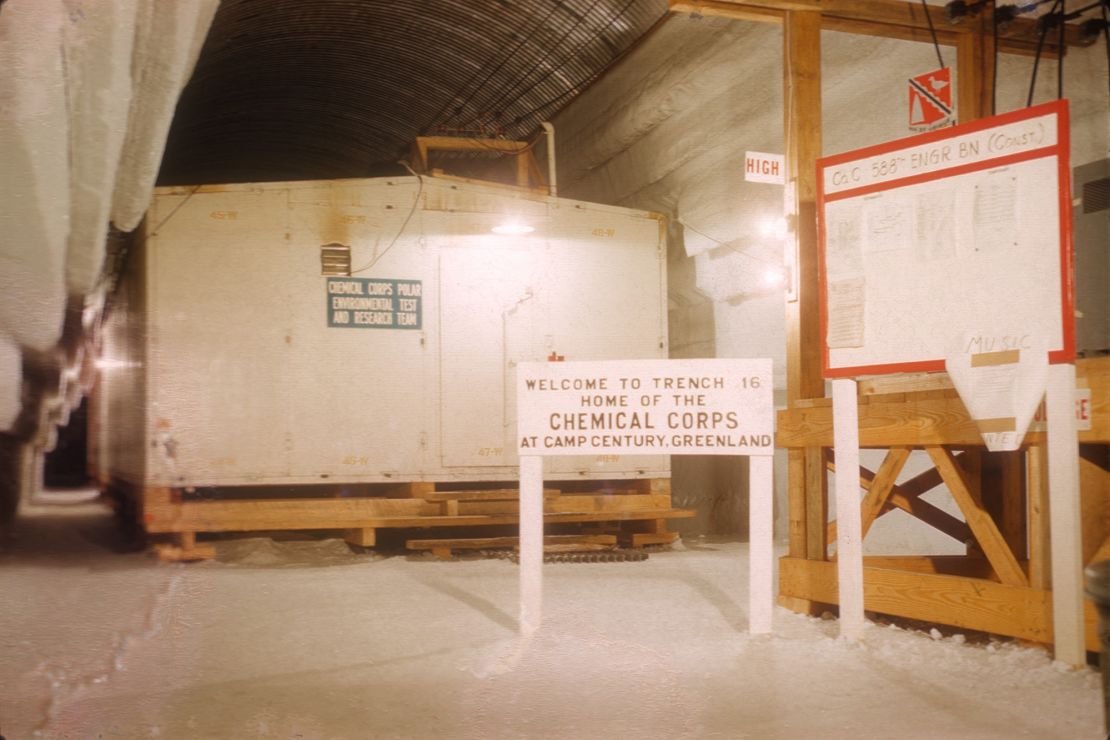

Heavy-duty machines with rotating shovels burrowed into the snow, creating a network of some two dozen tunnels. Prefabricated buildings erected in the underground caverns housed sleeping quarters, latrines, laboratories, a mess hall, laundry and gym. A nuclear reactor, transported slowly for 138 miles (222 kilometers) across the ice sheet and installed beneath the surface, powered the base.

Living in an ice sheet was not as harsh, or as onerous, as Weiss had initially feared. Inside the huts, it was warm and dry. Since most of Camp Century’s population of nearly 200 men was between the ages of 20 and 45, medical emergencies demanding his attention were rare. Weiss spent his free time studying medical textbooks, playing chess and bridge, and drinking 10-cent martinis. The food, he said, was “outstanding.”

“Living conditions were typically good (even though) you were in, you were under the snow. There was a big tunnel you could drive a truck into it, into the campus, and it was a long tunnel,” Weiss recalled.

Water — the camp needed about 8,000 gallons (some 30,000 liters) a day — came from a well dug in the ice with a drill that produced hot steam. Similarly, sewage was pumped down into a hole in the ice sheet.

Shortly after it became operational in 1960, the nuclear reactor was shut down as radiation in parts of the camp rose to unacceptable levels. Lead was shipped in to better protect the reactor’s components. Officials had ironed out those problems by the time Weiss arrived, and he didn’t remember being fazed about living close to a nuclear reactor.

“We were told that one of the main aims of Camp Century was to prove that an isolated installation could (be) safely and efficiently powered by nuclear energy. We thought it was safe, and no one told us otherwise,” he said.

Weiss rarely had cause to go the windswept surface. “I could stay in the hole, the trench, for weeks and never come out,” he said. “I had no reason to be up there. But I did sometimes go up there with other officers to see what was going on. I had a camera and took many pictures.”

Officers could spend up to six months at a time at the research station, while enlisted men could only spend four months. Despite the cocktails and nightly movies that Weiss vetted as the camp’s designated film censor, he said isolation took a psychological toll on some men. A popular joke among the troops was that “there was a pretty girl hiding behind every tree.” According to the 2021 book “Camp Century: The Untold Story of America’s Secret Arctic Military Base Under the Greenland Ice,” authored by Danish historians of science Kristian H. Nielsen and Henry Nielsen, only one woman even set foot there — a Danish doctor.

Camp Century operated continuously between 1960 and 1964, and then during summers only until its closure in 1967. The station’s public mission was scientific research.

The base itself was a study in the feasibility of long-term human habitation on the ice sheet. Other fields of scientific inquiry, according to Nielsen and Nielsen’s book, included the phenomena around the magnetic north pole and how they might affect communication channels, the geophysics of the ice sheet and how to identify dangerous glacier crevasses, and experimenting with cloud-seeding and other techniques as ways to mitigate treacherous whiteouts.

The US military actively publicized its achievements at Camp Century. Military officials hosted several journalists, who wrote stories celebrating the technical marvel the camp represented. Those ranks included Walter Cronkite, who visited and produced a CBS television documentary about the facility before Weiss’ arrival. Weiss later met Cronkite and said the pair exchanged stories about their time at Camp Century. The camp also welcomed two Boy Scouts: one from Denmark, which then controlled Greenland, and one from the United States, who spent the winter of 1960 on the ice sheet after winning a competition.

But behind the Cold War pomp and propaganda, Camp Century formed a testing ground for a clandestine mission known as Project Iceworm.

The bold plan envisioned a network of missile launch sites linked by a tunnel system under the Arctic ice that could potentially reach targets in Russia with greater precision. The project’s goal was to eventually cover an area of 52,000 square miles (about 135,000 square kilometers) — around the size of Alabama — with the ability to deploy some 600 missiles.

Weiss said he witnessed what in hindsight was likely a failed effort to create a key plank of Project Iceworm, a way to move the missiles around under the ice while avoiding Russian surveillance: a subsurface railroad. He recalls unsuccessful attempts at the railroad’s construction taking place in a horseshoe-shaped tunnel excavated under the ice, which was tested to understand what kind of loads it could bear.

Project Iceworm only became public knowledge in 1997, when the Danish Institute of International Affairs obtained a declassified set of US documents in connection with a larger study of the role Greenland played in the Cold War, according to Nielsen and Nielsen’s book. No missiles ever made it to the snowy wilds of Camp Century, although nuclear missiles were stored at Thule Air Base — a US military outpost known today as Pituffik Space Base, located at the ice sheet’s northwestern edge — a move that triggered outrage in Greenland and Denmark when it became public.

The plan is also mentioned in a book titled “The Engineer Studies Center and Army Analysis: A History of the U.S. Army Engineer Studies Center, 1943-1982,” which was published in early 1985, said Eric Reinert, a curator at the Office of History, Headquarters, US Army Corps of Engineers. He added that it was possible material associated with Project Iceworm is still classified or awaiting declassification. The Pentagon did not respond to a request for comment.

A full accounting of the scope of Project Iceworm remains sorely lacking, Kristian Nielsen said.

“Project Iceworm deserves a much bigger history because we only really have this one document that describes it. We don’t really have the original Project Iceworm documents,” said Nielsen, who is an associate professor at Aarhus University in Denmark.

“We don’t know who discussed it and who developed the idea. It’s hard to really assess how seriously it was taken and whether it was only in a very small circle of people who dreamed of this possibility.”

What’s more, it’s not clear whether Project Iceworm birthed the idea of Camp Century or vice versa, he added. “A lot of people seem to think that Project Iceworm was the big scheme behind Camp Century, but I’m thinking that Camp Century was already underway and then they thought, OK, what if we expand this.”

Weiss said he heard nothing about Project Iceworm during his stints at Camp Century.

“I’m not sure I even knew the word Iceworm in 1962 or ’63. I did not know about any missiles or nuclear stuff that was to be declassified later, but we were told that they wanted to run a subway under the surface of the ice,” Weiss said.

Greenland, which is now an autonomous territory in the Kingdom of Denmark, remains strategically appealing to the United States. President Donald Trump has revived calls made in his first presidency for US ownership of the island, which occupies a unique geopolitical position between the US and Europe and is rich in certain natural resources — including rare earth metals, which may become easier to access as the climate warms.

“(Greenland) is not necessary to launch an attack against Russia or any other country, because you can do that in other ways, mostly nuclear submarines and long-range missiles. But Greenland is still quite strategic in terms of surveillance, and it’s important for transport routes with the melting of the Arctic,” Kristian Nielsen said.

The effort and expense of maintaining a network of miles of tunnels in the ice cap was a deciding factor in the decision to shut down Camp Century in 1967. The elements were slowly crushing the base as the gradual movement of the ice sheet deformed the structures. As a result, the tunnels became narrower over time. Weiss recalls that “shaving” tunnel walls and transporting the heaps of ice and snow to the surface took up a lot of time and resources at the camp, which had a dedicated snow maintenance crew.

While Camp Century was an adventure he never sought out, for Weiss, it proved to be a turning point. The hours he spent in his bunk in the ice gave him time to widen and deepen his studies; he ultimately chose to focus on what has been a highly successful career in urology. Weiss no longer treats patients but is still actively writing grant proposals and scientific papers.

Camp Century’s scientific legacy also endures, particularly in climate research. Over the course of seven years, scientists stationed at Camp Century drilled the first core of ice that captured the full thickness of the ice sheet — a depth of 4,560 feet (1,390 meters) — and included some sediment from the ground below. Although subsequent ice cores have provided more detailed information, it represented the first archive of past climate conditions going back more than 100,000 years.

Similar to how tree rings reveal climatic conditions of years past, from a core of ice scientists can discern annual variations in snow and ice, and oxygen isotopes contained in air bubbles can be used as a temperature indicator.

“Back in ’66 when the ice core came out, what we didn’t know much about past climate was a lot,” said William Colgan, a Canadian professor of glaciology based at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, who describes Camp Century as the birthplace of paleoclimatology.

“That first ice core started us on the path to understanding Earth’s paleoclimate. It’s hard to understate. Now when we look at our atmospheric CO2 and we place it in that 800,000-year context, that’s coming from ice cores. Back in 1966, we didn’t even have 1,000-year context,” he said.

Paul Bierman, a professor and geomorphologist at the University of Vermont, agreed, describing the drilling of the ice core, and the 1969 paper spilling its secrets, as a stunning achievement. The findings resulted in what was effectively a frozen Rosetta stone, allowing scientists to understand in detail the climate over the past 100,000 years and beyond.

“That is probably still the most influential paper in climate science, if you had to pick one,” said Bierman, who is the author of “When the Ice Is Gone: What a Greenland Ice Core Reveals About Earth’s Tumultuous History and Perilous Future.”

Colgan visited Camp Century for the first time in 2010 to drill an additional ice core covering the period from 1966 to present day. That trip left him wondering about what was left of Camp Century in the ice beneath his feet.

Colgan returned to the location of Camp Century and subsequently embarked on a multiyear project to log and understand whether the biological, chemical and radioactive waste and physical debris left behind when Camp Century closed were at risk of being exposed as the climate warmed.

The US military removed the nuclear reactor that powered Camp Century, but batches of radioactive wastewater had been discharged into a cavity in the ice sheet during its years of operation. Additionally, the sewage produced by the camps’ inhabitants is still contained in the ice.

It’s not clear whether that waste and debris will remain entombed in the ice forever. Colgan’s projections, described in a 2016 study and a subsequent 2022 study, indicate that the site will experience no significant melt before 2100. This projection could change after 2100 if the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius is not adopted, he said.

The core extracted from Camp Century nearly five decades ago is still yielding new information. While much of the sample was destroyed during the initial phase of study, remaining segments are stored near Denver at the National Science Federation Ice Core Facility, after spending a stint at the University of Buffalo in upstate New York. However, sediment from the very bottom of the ice core that researchers had lost track of after it left Buffalo in the 1990s unexpectedly turned up in 2017 stored in glass jars in a freezer in Copenhagen.

Bierman was invited to study some of the sample, and he recalled melting the frozen sediment back in his Vermont lab in 2019 as his career’s only “eureka moment.”

His analysis revealed fossilized plant remains in the sediment — bits of twig, leaves and mosses which he said offered the first direct evidence that a large part of Greenland was ice-free around 400,000 years ago, when temperatures were similar to those the world is approaching now.

“We actually have plants and bugs, things that tell you that the ice was gone,” he said.

The study overturned previous assumptions that most of Greenland’s ice sheet has been frozen for millions of years and suggests the possibility of alarming sea level rise if it were to melt completely.

For Bierman, the science conducted at Camp Century is the station’s most powerful legacy. He said almost 100 scientific papers had been published by scientists based on work done at what he described as a unique outpost of humanity.

“This core lives on. Everything else at the camp is crushed and most of the people (who worked there) are dead,” Bierman said. “It lives on in a way that is telling us, at a time we absolutely need to know how the Greenland Ice Sheet behaved in the past, when that body of ice was gone.”

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.